NEP 2020 boldly championed digital learning as a key equalizer. Platforms like DIKSHA and PM e-VIDYA were projected as engines of universal access. Yet, five years later, India’s digital revolution in education looks dangerously uneven — even exclusionary.

When the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 was unveiled, it was hailed as the most transformative reform in India’s educational history in over three decades.

With grand promises of turning India into a “global knowledge superpower,” the policy pledged to foster equity, access, affordability, quality, and accountability across all levels of education.

From foundational literacy to multidisciplinary higher education, from digital classrooms to vocational integration, NEP 2020 appeared to be a roadmap for a truly 21st-century education system.

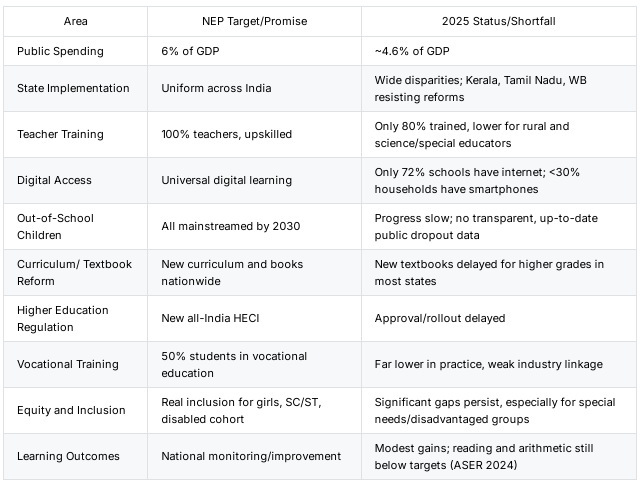

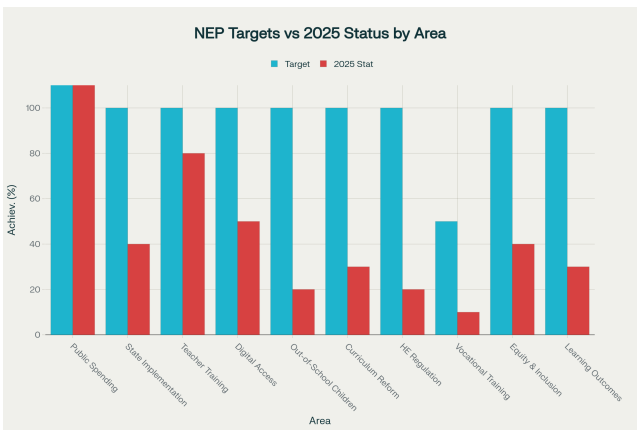

Five years later, however, the glow has faded. For all its promise and potential, NEP 2020 has stumbled at critical junctures. While certain flagship schemes have shown signs of progress, the broader vision remains largely unrealized, undermined by poor infrastructure, fragmented implementation, underfunding, and a troubling centralization of authority.

This article is not about what NEP got right it is about what the government failed to deliver, and why that failure must be called out now.

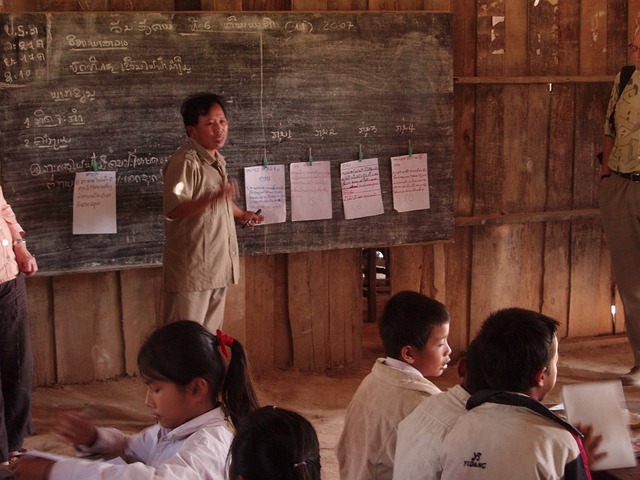

The Rural Digital Mirage: India’s Two-Speed Education System

NEP 2020 boldly championed digital learning as a key equalizer. Platforms like DIKSHA and PM e-VIDYA were projected as engines of universal access. Yet, five years later, India’s digital revolution in education looks dangerously uneven — even exclusionary.

Consider this: As per UDISE+ 2023-24, only 53.9% of schools in India have internet access. Even more shocking, 1.52 lakh schools still lack functional electricity.

Without electricity, the promise of tablets, smart classrooms, and online platforms is pure fiction. How does a teacher in rural Jharkhand deliver digital content when their school cannot even charge a device?

Urban private schools have embraced digital tools. Meanwhile, rural government schools struggle with blackboards, not bandwidth. The divide is no longer just digital — it’s systemic. This is how NEP has unintentionally created a two-speed education system: one racing ahead, the other stuck at the start line.

And while schemes like Smart Classrooms and ICT Labs have been sanctioned — over 82,000 and 1.2 lakh respectively — actual deployment, especially in low-income districts, remains poor. The digital dream, without infrastructure, has become a digital mirage.

If the government truly believed in equitable digital education, it would have led with power, connectivity, and hardware. Instead, it led with apps and slogans. The result? An entire generation of children in under-resourced regions is being left behind in a policy built to “include” them.

The NEP’s Centralized Push Is Weakening India’s Federal Fabric

NEP 2020 was supposed to be a framework of cooperative federalism. After all, education is a Concurrent List subject, requiring collaboration between Union and state governments. But the policy’s implementation has exposed a creeping centralization that threatens India’s constitutional federal balance.

Several opposition-ruled states — Tamil Nadu, Kerala, West Bengal — have resisted adopting NEP 2020, citing “Hindi imposition”, dilution of state curriculum autonomy, and disregard for local languages and pedagogies.

Tamil Nadu, for instance, categorically rejected the three-language formula, viewing it as a political tool rather than a pedagogical necessity.

Instead of negotiating with states, the Centre retaliated. In 2023, it reportedly withheld funds under the Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan and denied access to the PM-SHRI scheme to non-compliant states. This “comply or lose funding” approach reflects coercion, not collaboration.

Moreover, the promised Higher Education Commission of India (HECI) — envisioned as a single-window regulator — remains stalled, but fears persist that it will further centralize control at the cost of institutional autonomy.

This top-down execution undermines the NEP’s spirit. By prioritizing uniformity over diversity, the policy ignores India’s complex educational landscape. What works in Gujarat may not work in Manipur? What Delhi mandates may not align with Kerala’s needs.

If NEP 2020 is to succeed, the government must stop treating states as executors and start engaging them as equal stakeholders. Otherwise, we risk creating a “two-speed education federation” — compliant states with full access and dissenting states left out in the cold.

Vocational Education: A Target Without Teeth

NEP 2020 set a bold target: 50% of all learners should have exposure to vocational education by 2025. This was a much-needed shift in a country where formal education is too often decoupled from employability. But five years later, that target lies in tatters.

A study in Hailakandi district, Assam, reveals that 90% of schools lack vocational offerings. Only 10% provide even basic skill-based instruction. And yet, 100% of respondents in the study agreed that vocational education was necessary. This shows not a lack of demand — but a systemic failure in supply.

Even worse, 30% of respondents believed there wouldn’t be enough trained vocational teachers. 94% felt there wouldn’t be sufficient funds, especially in private colleges, to scale these programs. And 66% said industries weren’t ready to offer meaningful employment to vocationally trained students.

This is not a policy issue — it’s a governance failure. For a vocational ecosystem to work, you need qualified trainers, aligned curriculum, modern labs, real internships, and industry partnerships. None of these exist at scale.

In effect, NEP’s vision of mainstreamed vocational training has remained confined to pilot programs and aspirational charts. Without radical and urgent investment in TVET (Technical and Vocational Education and Training) ecosystems, the 2025 target is not just unachievable — it’s delusional.

If India fails to make vocational education viable and scalable, we’re staring at a future with degrees but no jobs, classrooms but no skills — a dangerous mismatch in the making.

Where Are the Teachers for the New India?

NEP 2020 envisioned a reformed teaching workforce: highly trained, well-compensated, and digitally empowered. It mandated a 4-year B.Ed. degree by 2030, minimum 50 hours of CPD (Continuous Professional Development) annually, and equipped teachers with ₹10,000 tabs. On paper, it sounded revolutionary.

Reality tells a different story.

Yes, over 1.4 million teachers have been trained under NISHTHA, but training alone does not equate to capacity building. Many teacher associations report that educators haven’t received revised textbooks, nor have they been provided with practical training aligned with NEP’s curricular shifts.

Infrastructural readiness is also a major gap. How can teachers adopt digital pedagogy when half their schools lack computers or internet? How can they conduct assessments via Holistic Progress Cards if they’ve never used the PARAKH framework?

Moreover, the pipeline for new educators is weak. B.Ed. colleges remain uneven in quality, and regulatory oversight is patchy. Rural and tribal areas face chronic shortages, especially for STEM and language teachers. Despite the emphasis on multilingual teaching, we don’t have enough teachers fluent in both mother tongues and standard academic languages.

Simply put, the new India NEP imagines doesn’t have the teachers it needs. The government has grossly underestimated the scale of transformation required in teacher education and support systems.

Empowered educators are the backbone of any reform. Without meaningful investment in recruitment, retention, and upskilling, NEP 2020 is a car with no driver.

MPhil Is Dead. Is Indian Research Next?

NEP 2020 discontinued the MPhil degree, aiming to streamline higher education. While well-intentioned, this abrupt move has left a vacuum in academic mentorship and research preparation.

PhD enrolments have surged — 2.34 lakh students in 2022-23 — and India now ranks 3rd globally in research publications. Sounds impressive? Dig deeper. Only 10 Indian universities rank in the top 50 globally in subject-wise QS rankings. India has quantity, not quality.

The removal of MPhil has inadvertently cut off a critical bridge between coursework and doctoral research. MPhil was not just a degree — it was a training ground for academic inquiry, literature review, methodology, and thesis writing. Now, students enter PhDs unprepared, straining already overburdened supervisors.

Moreover, while patent filings reached 92,168 in 2023-24, only 25% came from higher education institutions. Innovation councils (IICs) have expanded, but the link between research and real-world impact remains tenuous.

The government is also pushing for foreign university campuses (Deakin, Wollongong, Southampton), but what about capacity-building within Indian HEIs? Most institutions lack world-class labs, competitive grants, and research autonomy. Funding under PM-USHA (₹100 crores per university) is spread too thin.

NEP aimed to make India a knowledge superpower. But if we’re dismantling research training structures without building new ones, we risk an ecosystem of publish-or-perish without purpose. The MPhil vacuum is just one symptom — the deeper disease is a broken pipeline from classroom to lab to global impact.

Assessment Reforms: A Case of One Step Forward, Two Steps Back

NEP 2020 promised to reinvent the assessment system — moving away from rote memorization to competency-based, formative, and holistic evaluation.

It introduced PARAKH to standardize learning outcomes and proposed only three key exams in Classes 2, 5, and 8, alongside biannual board exams for Classes 10 and 12. The promise? Lower stress, deeper learning.

Five years later, the results are underwhelming.

The Holistic Progress Card (HPC) designed by PARAKH has been adopted by 26 states/UTs, but its implementation is fragmented. In private schools, some adoption exists. In government schools, many educators are not even aware of the HPC framework. Reasons? Poor digital infrastructure, inadequate training, and lack of awareness.

Meanwhile, the new biannual board exam model (from 2026) has sparked concern. Schools are overwhelmed by logistical complexities, increased evaluation loads, and emotional pressure on students and teachers alike. Without robust preparation, this well-intentioned reform may worsen exam anxiety — not reduce it.

Furthermore, the CUET (Common University Entrance Test) has faced criticism for encouraging coaching culture. Faculty from public universities argue that CUET has distorted admissions, creating a bias toward elite institutions while leaving smaller colleges with vacant seats.

The NEP rightly identified assessment as a lever for transformation. But the shift from “marks-based” to “mastery-based” needs more than structural redesigns — it demands ecosystem readiness, teacher training, student awareness, and supportive tech infrastructure. Without these, the reform risks becoming a cosmetic change, not a cognitive one.

Underfunded, Underutilized: The NEP’s Achilles’ Heel

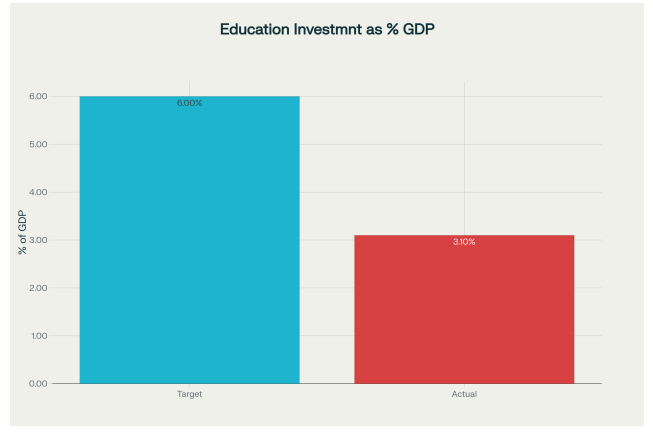

Perhaps the most glaring indictment of NEP 2020’s journey is the government’s failure to back ambition with money. The policy itself recommended 6% of GDP be allocated to education. As of 2024-25, the actual figure remains stubbornly around 3%.

This funding gap is not trivial. NEP’s success depends on new infrastructure, digital tools, teacher salaries, training programs, curriculum development, vocational labs, and research support. All of these require massive investment — none of which is possible at half the promised allocation.

Even worse, the funds that are allocated aren’t being fully used. Between 2018-19 and 2023-24, an average of 15% of Samagra Shiksha funds remained unutilized. Bureaucratic red tape, weak capacity in states, and delayed disbursals are to blame.

The Union Budget 2025-26 saw a 6.5% rise in education allocation — the lowest increase in four years. At a time when inflation, enrollment growth, and digital demands are rising, this indicates a worrying deceleration in political will.

Vocational education is especially underfunded. In the Hailakandi study, 94% of respondents believed private colleges lacked sufficient financial support to implement skill-based education.

The numbers don’t lie. The government’s spending tells a story of rhetoric over resolve. No amount of policy vision can substitute real fiscal commitment. Until India starts putting its money where its mouth is, NEP will remain an ambitious document — not a transformative revolution.

Language, Identity, and the NEP’s Most Polarizing Fault Line

NEP 2020 promotes multilingualism, suggesting education in the mother tongue/local language until Grade 5 (preferably Grade 8). It explicitly avoids mandating any language. Yet, in practice, this has become the most divisive feature of the policy.

States like Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and West Bengal have accused the Centre of pushing Hindi and Sanskrit, interpreting the three-language formula as covert linguistic imposition. Tamil Nadu, in particular, has been vehement — reaffirming its two-language policy and refusing to adopt NEP’s language norms.

The political backlash aside, implementation feasibility is a genuine concern. India has 22 scheduled languages, hundreds of dialects, and a severe shortage of multilingual teachers and materials. Crafting textbooks and training educators in regional languages at scale is a herculean task — one the government has not adequately prepared for.

Moreover, the Commission for Scientific and Technical Terminology (CSTT) has digitized 16 lakh technical terms across 22 Indian languages. But quantity does not ensure usability — are these terms accessible to students? Are teachers equipped to use them in a classroom?

Multilingual exams like JEE and CUET in 13 and 12 languages respectively are a welcome step. But the infrastructure to support such diversity — translators, evaluators, digital platforms — remains uneven and ad hoc.

Language policy in a country as diverse as India needs inclusivity, flexibility, and cultural sensitivity. Instead, NEP’s language vision, though progressive on paper, has become a lightning rod for regional resentment, further polarizing an already fragile consensus.

Conclusion

NEP 2020 is not an ordinary policy. It is — or was — India’s moonshot in education, promising equity, excellence, and employability for all. But five years in, that vision risks implosion from within.

The government has failed to deliver on its own benchmarks: from digital infrastructure to vocational training, from teacher capacity to research support, from cooperative federalism to financial commitment. What should have been a blueprint for a new India now resembles a case study in policy overreach and execution underperformance.

The real tragedy? Millions of students — especially from rural, tribal, and low-income communities — will bear the brunt of these failures. Not the policymakers.

If the government still believes in NEP’s promise, it must shift from symbolism to substance, from control to collaboration, and from incrementalism to investment.

India cannot afford another lost decade. NEP 2020’s window is still open — but not for long. The time for excuses is over. The time for accountability is now.