Education Budget 2026 expectations from the skilling sector must therefore focus on quality and alignment rather than volume. Apprenticeships need to be treated as mainstream education pathways, not peripheral schemes.

As India approaches the Union Budget 2026, education once again occupies a prominent place in public discourse. This attention is not accidental.

It reflects a growing recognition that India’s future economic and social trajectory is now inseparable from the performance of its education and skilling systems.

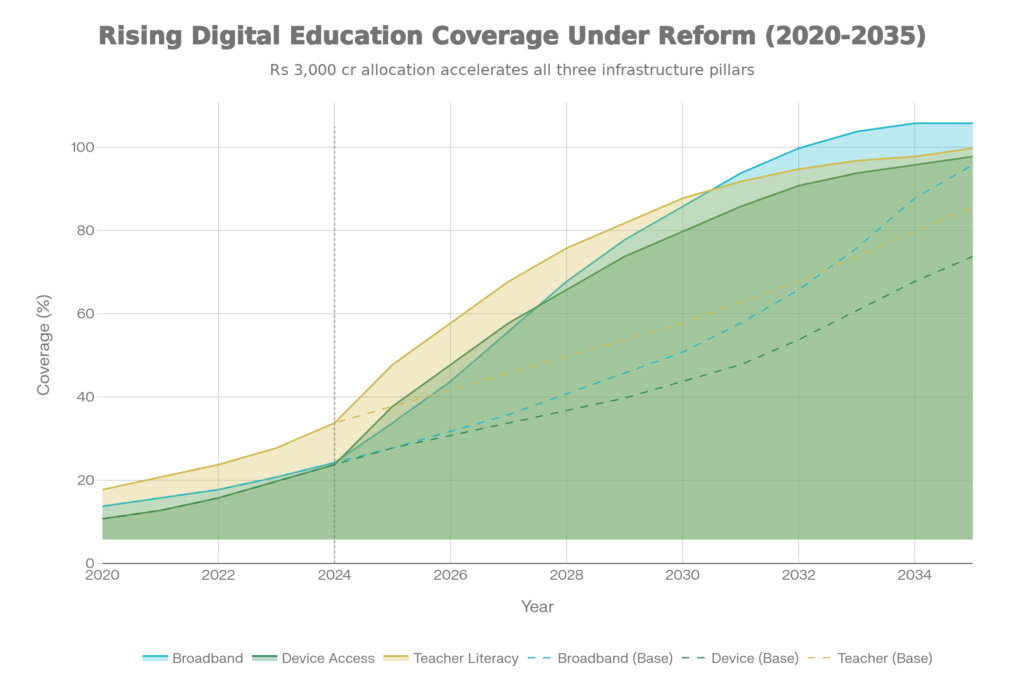

Over the last decade, India has expanded access to education at a scale rarely seen in history. School enrolment has reached near-universal levels, higher education enrolment has crossed 43 million students, and digital learning platforms now reach tens of millions of learners across geographies.

Yet, the data tells us something more sobering. Despite this expansion, learning outcomes remain uneven, graduate employability is weak, and social mobility through education is increasingly uncertain.

India spends between 4.1 and 4.6 percent of its GDP on education, a figure that meets minimum global benchmarks but falls short of the country’s own stated ambition of 6 percent. More importantly, the effectiveness of this spending remains contested.

Budget 2026 therefore arrives at a moment of reckoning. The central challenge is no longer whether India can scale education, but whether it can translate scale into meaningful learning, productive employment, and equitable opportunity.

The expectations of online education providers, EdTech firms, study abroad stakeholders, and the skilling sector must be read against this larger question: how public finance can move India from an education system defined by expansion to one defined by outcomes.

Scale and The Limits of Expansion-Led Education Policy

India’s education system today is defined by scale. Approximately 250 million children are enrolled in schools, and nearly 580 million Indians fall within the 5–24 age group.

Higher education Gross Enrolment Ratio has risen steadily from 23.7 percent in 2014–15 to 28.4 percent by 2021–22, placing India among the fastest-growing higher education systems globally. Female participation has reached near parity in many states, and regional disparities in enrolment have narrowed.

However, learning data complicates this success story. ASER and National Achievement Survey results consistently show that a large proportion of children in primary school struggle with basic reading and arithmetic.

Even before the pandemic, nearly half of Grade 5 students could not read a Grade 2-level text. Post-pandemic assessments suggest that learning losses have pushed these figures further back, particularly in government schools serving low-income households.

Public expenditure on education, while significant in absolute terms, has not translated proportionately into learning outcomes. India’s spending level places it below countries that have successfully converted education into productivity gains, such as South Korea or Vietnam, which invested heavily in teacher quality and curriculum reform during their demographic transition phases.

The data reveals a structural imbalance. India has focused heavily on enrolling children and expanding institutions, but far less on ensuring that time spent in classrooms translates into mastery.

Budget 2026 expectations must therefore shift emphasis. The question is not how many learners the system reaches, but what those learners actually gain. Without addressing this imbalance, continued expansion risks creating a large pool of formally educated but functionally underprepared citizens.

Online Education and Edtech: Growth Without Guaranteed Learning

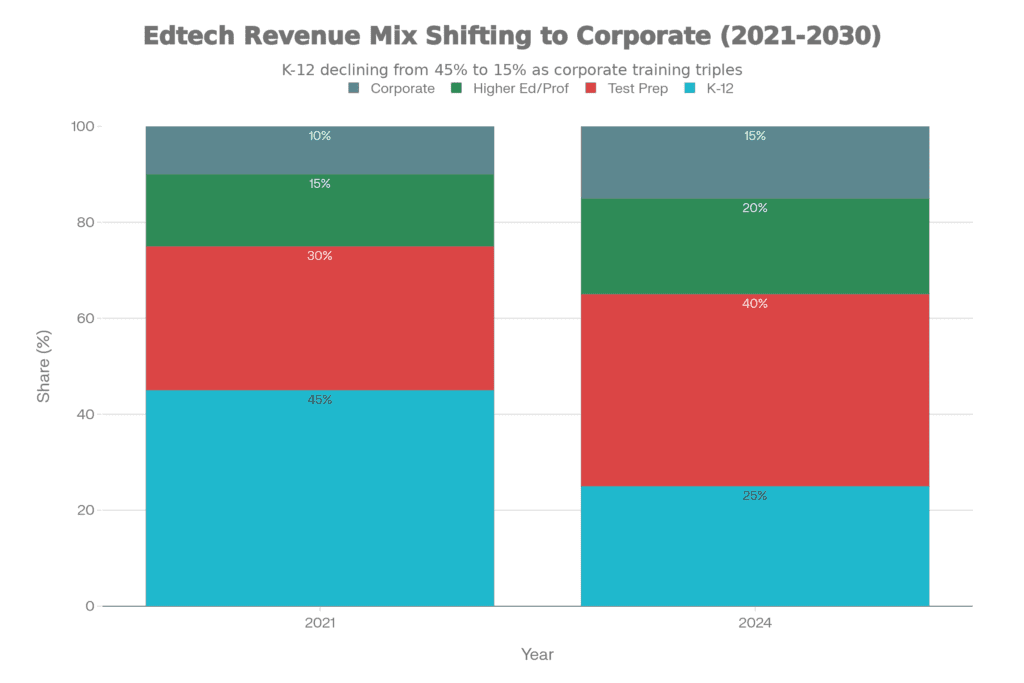

India is now one of the world’s largest markets for online education. The domestic EdTech sector, valued at roughly USD 7–8 billion, is projected to grow rapidly through the next decade.

During the pandemic, online platforms became the primary mode of instruction for millions of students, and even after reopening, hybrid learning has remained embedded in many institutions.

Yet evidence on effectiveness remains mixed. Surveys conducted during and after the pandemic show that students from higher-income households with access to devices, stable connectivity, and parental support benefited far more from online learning than first-generation learners or younger children.

ASER data indicates that children in private schools experienced smaller learning losses than those in government schools, suggesting that digital access and home support played a decisive role.

The data therefore points to an important conclusion. Technology does not neutralise inequality; it often magnifies it. Digital platforms deliver content efficiently, but learning depends on pedagogy, feedback, and sustained engagement. Where teachers are unsupported or instructional design is weak, online learning replicates the limitations of traditional classrooms rather than overcoming them.

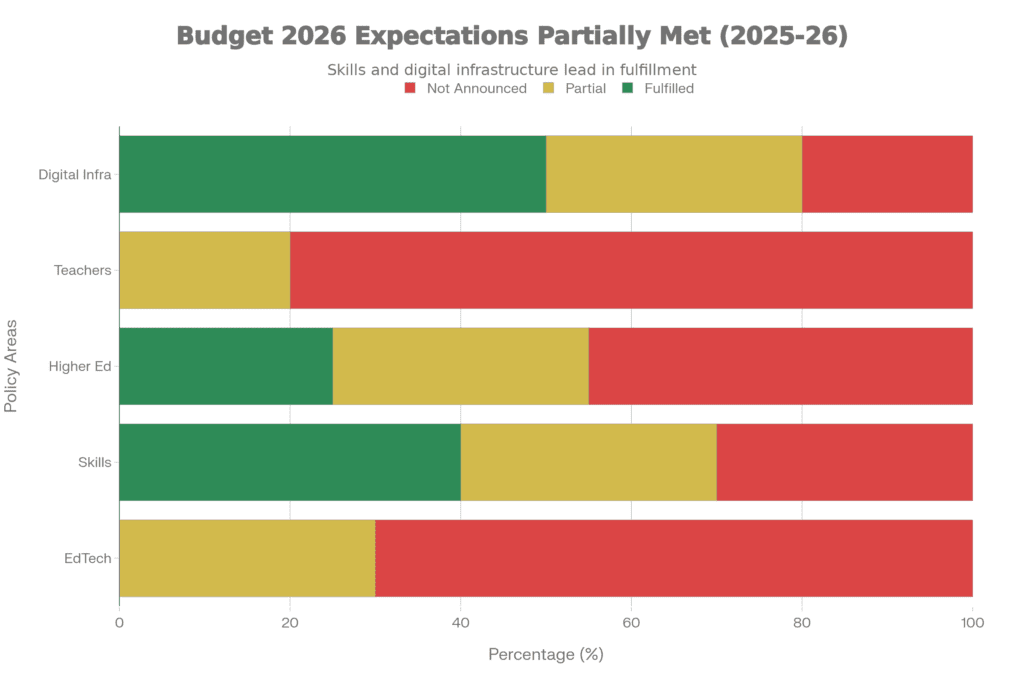

As part of Education Budget 2026 expectations for online education and EdTech, the sector seeks fiscal incentives, public partnerships, and regulatory clarity.

These are legitimate demands. However, public funding must be conditional on demonstrable learning improvement, especially for students at the bottom of the learning distribution. Without outcome-linked financing and independent evaluation, public investment risks subsidising scale rather than substance.

Skilling and Employability: When Certification Outpaces Capability

India’s skilling ecosystem has expanded rapidly over the last decade. Government programmes report that over 16 million individuals have received some form of skill training, and apprenticeship enrolments have increased significantly.

Despite this, labour market indicators reveal persistent distress. Graduate unemployment remains well above overall unemployment, and multiple employer surveys suggest that fewer than half of graduates are readily employable without additional training.

This mismatch reflects a deeper structural issue. Many skilling programmes prioritise enrolment and certification targets rather than employment outcomes. Completion certificates often do not correspond to workplace readiness, and wage progression after training remains modest for a large share of participants. The result is a proliferation of credentials with limited labour market value.

Data from periodic labour force surveys shows that a significant proportion of educated youth are either unemployed or employed in roles that do not utilise their education. This underemployment represents a loss both for individuals and for the economy.

International comparisons suggest that countries which successfully harnessed their demographic dividend did so by tightly integrating education, vocational training, and industry demand.

Education Budget 2026 expectations from the skilling sector must therefore focus on quality and alignment rather than volume. Apprenticeships need to be treated as mainstream education pathways, not peripheral schemes.

Public funding should reward sustained employment, wage growth, and employer satisfaction rather than certification counts alone. Without such recalibration, skilling risks becoming a parallel system disconnected from both education and employment.

Study Abroad: Aspiration, Affordability, And Domestic Capacity

India has become the world’s largest source of international students, with more than 1.8 million Indians currently studying abroad. Household spending on overseas education runs into tens of billions of dollars annually, often financed through education loans.

Recent policy measures, including adjustments to tax collection at source, reflect Education Budget 2026 expectations aimed at easing financial pressure on families.

However, the scale of outbound mobility also signals a deeper structural issue. Students increasingly view overseas education not merely as a status symbol, but as a rational investment driven by perceived gaps in domestic quality, research exposure, and global employability. Data shows that students are diversifying destinations, seeking countries with better post-study work options and lower total costs.

While financial relief measures are important, they address symptoms rather than causes. The long-term solution lies in strengthening Indian higher education itself.

Public investment in research infrastructure, faculty development, and international collaboration could reduce the perceived quality gap that drives students abroad. Countries that successfully retained talent during periods of globalisation did so by building strong domestic institutions rather than subsidising outward flows.

Budget 2026 must therefore balance support for student mobility with serious investment in domestic capacity. Without this balance, India risks normalising a system in which global opportunity is accessible primarily to those who can afford to leave.

Teachers and Institutions: The Most Decisive Yet Underfunded Lever

Across both school and higher education, teacher capacity remains the most critical determinant of learning outcomes. Data consistently shows that teacher quality has a larger impact on student achievement than class size, infrastructure, or technology.

Yet India continues to face chronic teacher shortages, particularly at the secondary level, where pupil-teacher ratios often exceed recommended norms.

In higher education, faculty vacancies, limited doctoral pipelines, and constrained research funding weaken institutional quality. India’s expenditure on research and development remains around 0.7 percent of GDP, significantly lower than comparator economies. This limits both knowledge creation and the ability of universities to attract and retain high-quality faculty.

Despite repeated policy recognition, teacher development remains underfunded and fragmented. Training is often episodic, disconnected from classroom realities, and insufficiently supported by mentoring or instructional resources. Institutions are frequently burdened by administrative compliance rather than empowered to innovate.

The Education Budget 2026 by Nirmala Sitharaman must therefore treat teachers and institutions not as cost centres, but as long-term assets. Sustained investment in professional development, research ecosystems, and institutional autonomy is essential if India is to improve learning outcomes at scale. Without this shift, investments in infrastructure and technology will yield limited returns.

Equity, Learning Poverty, And The Cost of Exclusion

Aggregate progress in education often masks deep and persistent inequities. Disaggregated data reveals significant learning gaps between rural and urban students, between children from different income groups, and across regions.

Learning poverty, defined as the inability to read a simple text by age ten, remains alarmingly high in India, particularly among children attending government schools.

Children with disabilities remain significantly underrepresented in enrolment and completion data, while gender parity in education has not translated into equivalent participation in the workforce.

These gaps carry long-term economic costs. The World Bank’s Human Capital Index suggests that a child born in India will be only about half as productive as they could be with complete education and health.

Budget 2026 must therefore place equity at the centre of education finance. Targeted investment in foundational learning, inclusive education, and regional capacity is not merely a moral imperative; it is an economic necessity. Countries that allowed learning gaps to persist during their demographic transition paid a lasting price in inequality and social fragmentation.

Without deliberate redistribution of resources toward the most disadvantaged learners, India risks creating a two-tier education system in which opportunity is determined less by effort and more by circumstance.

What The Data Cannot Fully Capture, And Why Judgment Matters

Data has become central to how we think about education policy. Enrolment ratios, learning outcomes, completion rates, placement statistics, and fiscal allocations now shape both public debate and budgetary decisions.

This shift toward evidence-based policymaking is welcome. Without data, systems drift on assumption and anecdote. Yet, data, by its very nature, captures only what is measurable. And in education, some of the most consequential elements remain only partially visible, if at all.

Large datasets can tell us how many children are enrolled in school, but not whether they feel safe, respected, or motivated to learn. Assessment scores can reveal learning levels at a point in time, but not the confidence a child gains from a caring teacher or the long-term curiosity that sustains learning beyond examinations.

Similarly, skilling data can report how many certificates were issued, but it cannot easily capture whether a young person gained dignity, agency, or the ability to navigate uncertainty in the labour market.

Data also struggles with absence. It rarely records those who leave the system quietly, children who attend school irregularly, adolescents who drift into informal work, or first-generation learners who abandon higher education after a semester without triggering any formal dropout flag. These invisible exits often represent the most serious policy failures, yet they remain statistically muted.

Judgment matters because policy decisions are ultimately about people, not indicators. Evidence can show trends, but judgment is required to interpret trade-offs, anticipate unintended consequences, and decide what should be prioritised when resources are limited.

For example, a technology intervention may show modest short-term learning gains, but judgment is needed to assess whether it undermines teacher autonomy or widens inequality over time.

Education as Intergenerational Infrastructure, Not an Annual Budget Item

Public discussions around education budgets are often confined to year-on-year increases, scheme allocations, or headline announcements. What the data rarely forces us to confront is that education functions more like intergenerational infrastructure than a recurring welfare expense.

Roads, ports, and power plants are designed with multi-decadal horizons; education systems, by contrast, are frequently planned within five-year political cycles. This mismatch has long-term consequences that short-term metrics cannot easily capture.

Evidence from longitudinal studies shows that early learning quality has effects that persist across decades, influencing lifetime earnings, health outcomes, and even civic participation.

The World Bank estimates that every year of quality schooling raises lifetime earnings by 8–10 percent, but these returns compound only when learning is sustained across stages. Fragmented funding, where early childhood, school education, higher education, and skilling are treated as separate silos, breaks this compounding effect.

India’s current approach reflects this fragmentation. Foundational learning programmes struggle for continuity, secondary education receives less attention than enrolment figures suggest, and skilling initiatives are often designed as short-term corrections rather than integral parts of an educational journey.

Budgetary thinking reinforces this fragmentation by allocating funds scheme by scheme, rather than investing in coherent learning pathways that span childhood to adulthood.

Judgment matters here because data alone cannot determine optimal sequencing across generations. Policymakers must decide whether to prioritise visible, short-term outputs or less visible investments whose returns emerge slowly but reliably.

Treating education as intergenerational infrastructure requires Budget 2026 to ask a deeper question: are today’s allocations building the conditions for sustained learning over 30 years, or merely financing the present system’s survival?

When Institutional Trust Matters More Than Institutional Choice

Contemporary education discourse often emphasises choice, more institutions, more courses, more platforms, more pathways. While choice can improve efficiency and innovation, data increasingly suggests that trust in institutions matters more for long-term outcomes than the sheer number of options available.

In societies where public confidence in schools and universities is strong, families invest time, effort, and patience in education even when short-term outcomes are uncertain.

In India, survey data reveals an erosion of trust in public education quality, despite high enrolment. Families hedge their bets through private tutoring, multiple coaching classes, or expensive overseas education, often at significant financial strain.

This behaviour is rational at the household level, but inefficient at the system level. It signals a lack of confidence that institutions will deliver consistent learning outcomes.

Trust cannot be legislated, and it cannot be built through rankings or promotional campaigns alone. It emerges when institutions demonstrate reliability over time, when children learn what they are expected to learn, when credentials translate into opportunity, and when grievances are addressed transparently.

Data can indicate where trust is weakening, such as rising private tutoring even among government school students, but it cannot rebuild trust by itself.

Budgetary decisions play a subtle but decisive role here. Underfunded schools, high teacher turnover, and unstable policy frameworks erode institutional credibility.

Conversely, predictable funding, professional autonomy for educators, and visible investment in quality signal seriousness and care. Judgment is required to recognise that restoring trust may not yield immediate political dividends, but it is foundational to any sustainable education system.

Conclusion

Education is not merely another sector competing for fiscal allocation. It is the moral and economic infrastructure of society.

The true test of Education Budget 2026 Expectations will not be market growth or digital adoption alone, but whether public investment improves learning, expands opportunity, and strengthens social cohesion.

The question Budget 2026 must answer is not how much India spends on education, but how wisely and for whom.

That answer will shape the country’s future far more than any headline allocation figure.